culture

Our Cultural Identity. Not Your Costume.

The other day, I walked into a Halloween store to grab some fake blood for my costume (my friends and I were the Heathers from the 1988 cult-classic film) and spotted a few white teenagers perusing the “Around the World” aisle. Each year as Halloween rounds the corner, I feel an intense residual frustration from summer festival season (cough-cough Coachella, cough Stagecoach) culminate into full-fledged outspoken rage. It’s this point in time when I feel a burning desire to speak up and recall something seemingly obvious—a concept which should be commonly understood by now—to the attention of my friends, peers and even strangers: cultural appropriation. So before you knock me as another easily-triggered millennial, or contest that it’s appreciation not appropriation, hear me out:

As I wander around the store, a giant rack of kitschy and apparently “Mexican-style” ponchos catches my eye, right beside the—I kid you not, “Tequila Poppin’ Dude” costume set complete with a sombrero, moustache, shot glass belt and fake tequila handles. The man modeling the costume in the photo is white. While some may find this costume funny, playing into the stereotype of Hispanic people as drunkards and mocking their appearance fuels racial discrimination and evokes cultural insecurity among people of colour (PoC). The act of assuming a single identity for an entire culture cannot be defended as appreciation; it is layered with disrespect and perpetuates the delusion of white exceptionalism.

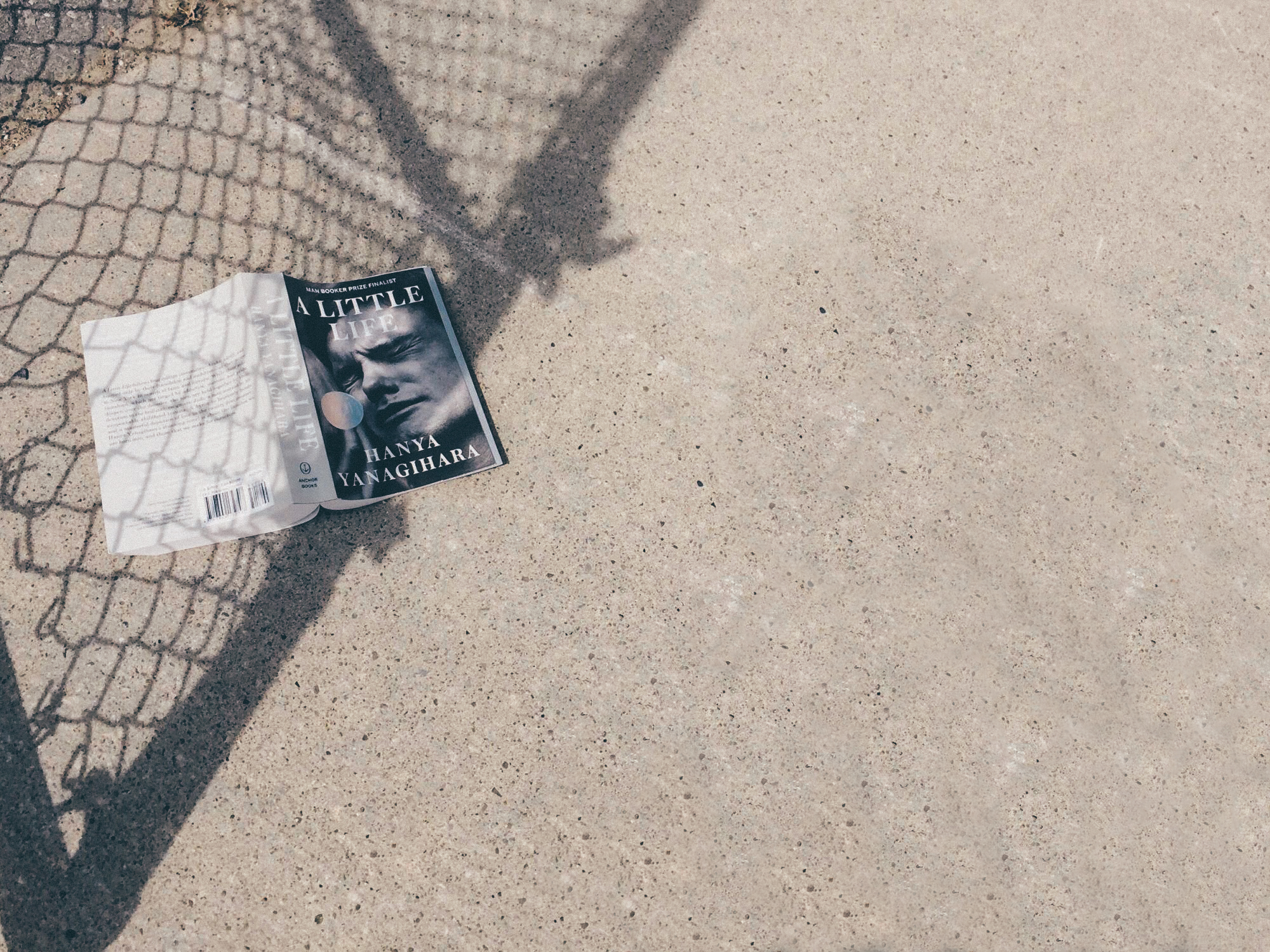

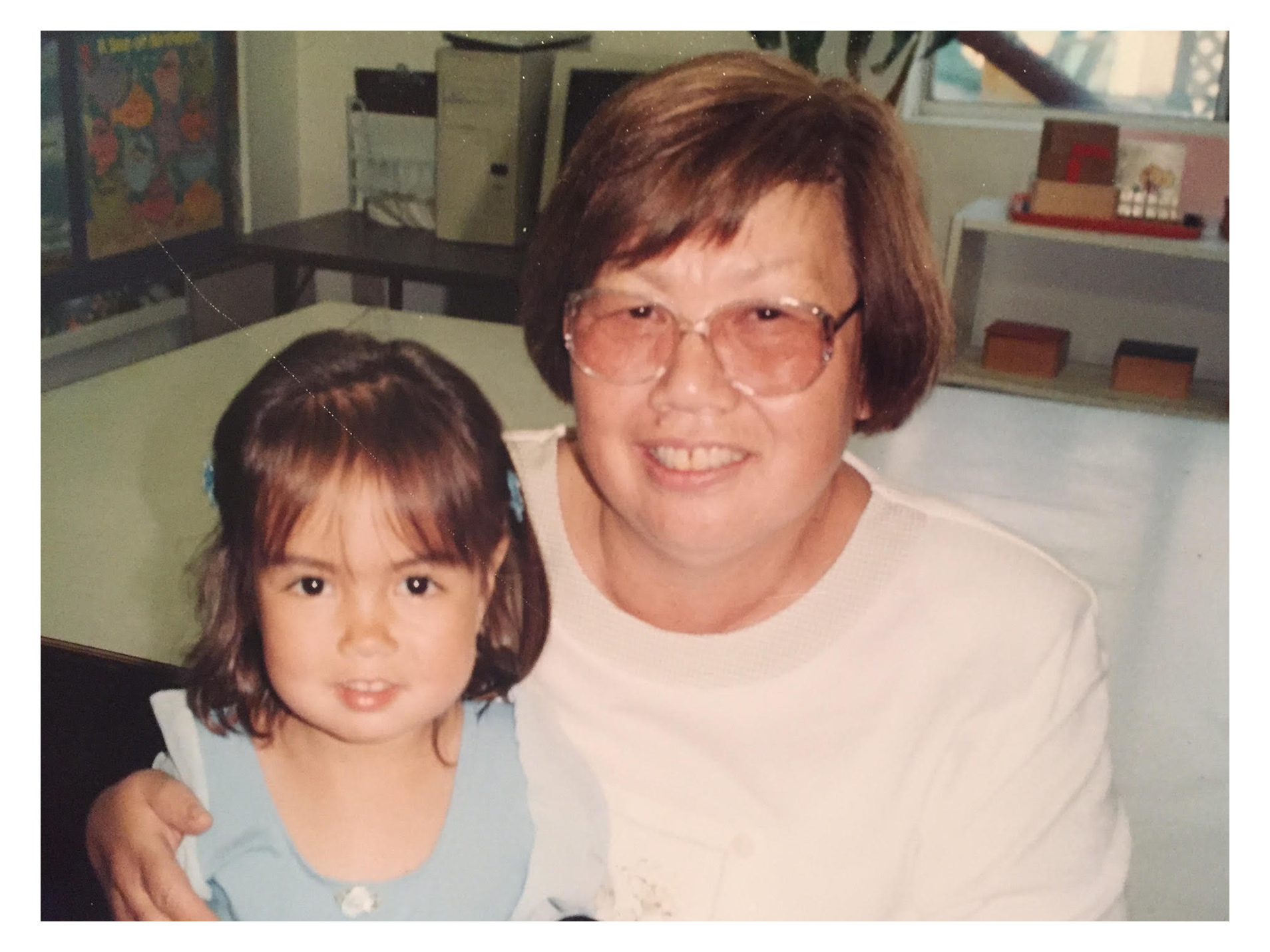

Photos of author’s grandmother, Ayako

Photos of author’s grandmother, Ayako

It’s as if to say: “I can be whomever I want for a day” without consequence and then return to a position of privilege. I prayed that someone of Mexican descent would not have to silently suppress humiliation in the face of a white man mocking their culture on Halloween. However, the western fascination with the “Other” combined with socially-embedded racism and historical subordination of PoC will perpetuate this highly offensive stereotype yet another year.

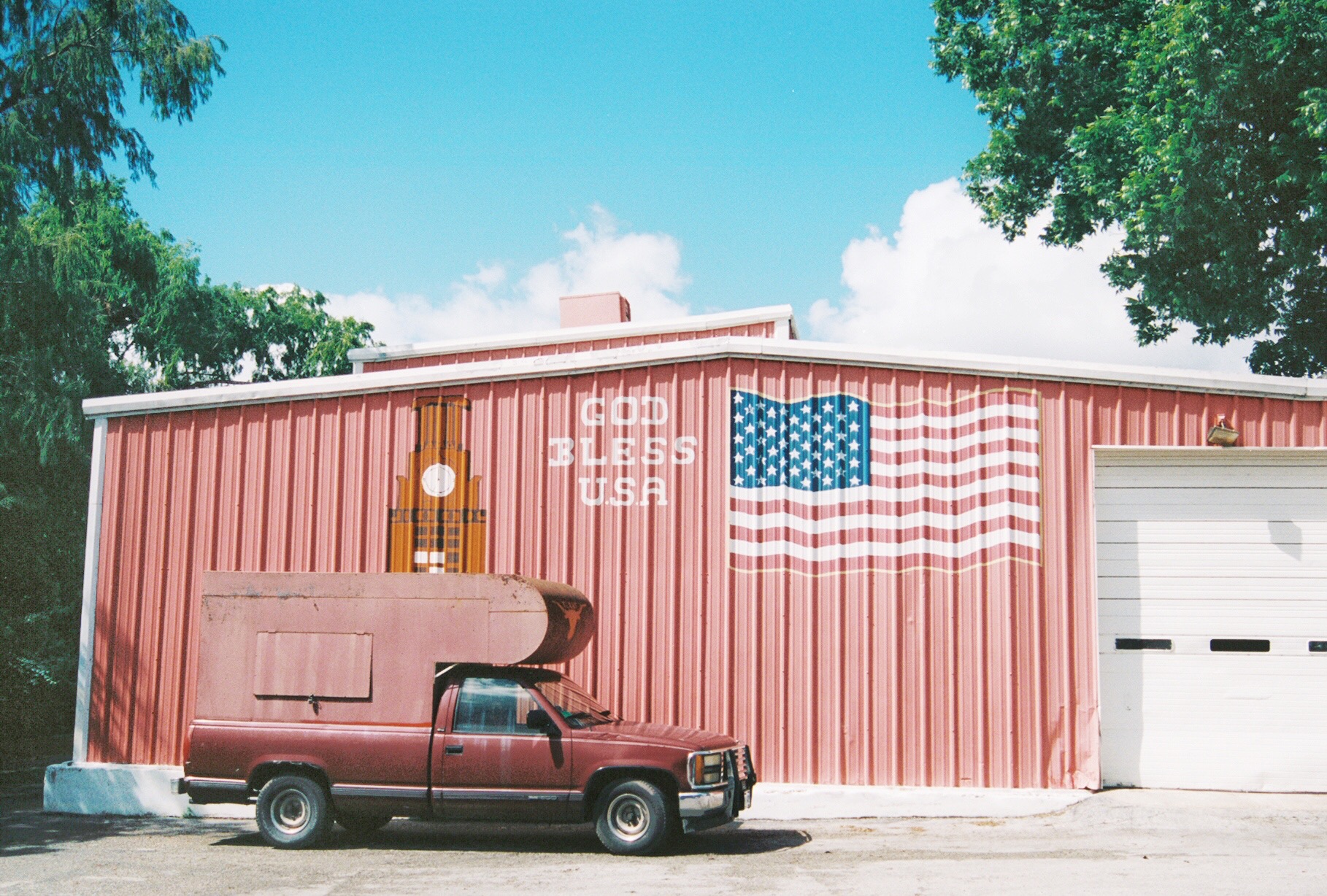

Seeing this costume on display front and center was especially disappointing because I live in Southern California, home to a large Hispanic population and major controversy over illegal immigration. This debate has always seemed ironic to me because Californians love to party in Tijuana and vacation in Baja, yet shut the doors to Mexican immigrants and if they manage to get in; we limit their economic and political opportunity. As Donald Trump continues xenophobic talk of building walls, inciting violence and perpetuating racism toward Mexican-American citizens, the white man’s conscious appropriation of the Mexican stereotype reaches a whole new level of prejudice this Halloween.

Behind me stood an entire wall of Native American costumes: “Western Deluxe Feather Headress[es],” “tribal” face paint, beaded vests, moccasins, fringe ponchos, bow and arrows, plastic axes and various other weapons, suggesting that all indigenous peoples are backwards savages. I thought back to a Buzzfeed video I had watched recently of Native Americans trying on a handful of “Indian” costumes. Now, I know what you’re probably thinking — Buzzfeed does tend to exploit PoC and often functions on the basis of racial stereotypes to gain views — but this video features actual Native American people speaking to the issue of cultural appropriation. I feel that their voices have more authority to explain the true offenses.

Although the speakers are unnamed (frustrating because it takes away their individual agency), one woman elaborates upon commercialized Native American costumes and their cultural-insensitivity: “When you see beads on an actual pow wow dress, every single pattern means something.” Another woman explains, “Because it’s so inaccurate, it almost feels like a joke — like someone is making fun of me and all the things my people died and fought to hold on to.”

The problem with cultural appropriation does not lie in the fact that a particular dress or appearance is exclusive to a single race or culture. The problem is that at the end of the day, non-people of colour can wipe off their “tribal warrior” face paint or take off their feathered headdresses and resume their privileged lifestyle. On the other hand, Native Americans cannot hide from racial discrimination and prejudice; it rides on their skin colour and although largely overlooked by white America, the painful history of continual oppression, stolen land and revoked human rights remains in their blood.

Turning around, my sight landed on a Geisha style wig with chopsticks and an assumed oriental-style, short, sleeveless halter dress with slits up the leg. I recalled photos of my Japanese grandmother in Fukuoka on her wedding day in 1965, dressed in traditional silk kimono as she disobeyed her parents, fled from arranged marriage plans and married my American grandfather for love instead. I laughed out loud, the reverberating sound a hollow echo of how I truly felt—disrespected. I eyed the obnoxious lime-green floral dress modeled by a white woman with chalky white face paint and garishly-painted red lips in the advertisement. Suddenly, my reaction felt insufficient. My expression twisted in pure disgust.

I pulled up the photo of my grandmother on my phone; she and the woman advertising the geisha costume looked nothing alike. I felt my cheeks flush and my eyes start to burn. Standing before this attempted replica, I felt insecure in my own skin. I pictured my beautiful, brave grandmother eager to begin a new life in the U.S. yet equally determined to maintain pieces of her Japanese culture to pass down to my brother and I. Her beautiful kimono possessed both personal and cultural significance yet here it was, being hemmed and unraveled into a cheap, flashy, sexualized rendition of Asian femininity right before my eyes.

At first, I hated the girl in this so-called Japanese costume, but the anger was misdirected; the real issue is the role of Orientalism in American society, which objectifies the purportedly exotic ‘Other’. Sure, sex sells, but not at the expense of cultural accuracy. For one, Geishas are not sexy nor prostitutes nor submissive. Traditionally, they spent years training to perform intricate shamisen music and entertain deeply intellectual conversation with Japan’s political elite. The role of the Geisha was a respected as a form of art and allowed women to have voice, agency and influence in a strict patriarchal society.

Secondly, kimonos are central to traditional Japanese culture, requiring hours and multiple hands to carefully dress, layer upon layer. The costume’s alterations are like a slap in the face to the artistry and history behind this Japanese tradition. Not only do these costumes objectify women through the capitalist male gaze, but with each wear, they reduce women of colour into commodified images of idealized, exotic, and submissive stereotypes.

I picked up the package and noticed that she even did her eyeliner so that her eyes would appear almond-shaped. How ironic that the Asian features for which I was made fun of as a child are now being commodified and made desirable (…or are they mocking them?) Why does my everyday appearance suddenly have appeal only when one can wipe off their makeup and return to the security of white features at the end of the night? How could anyone wear this costume, paint their face, and feel as if they were doing my culture any justice? My culture is not a costume. It stands for much more to my grandmother, to my mother, to myself, and to my people; it is a part of our identity that cannot and should not be replicated for Halloween or any other excuse.

Although Halloween is a time in which you are encouraged to pretend to be someone you are not, this does not necessarily mean you should. Appropriating a look that attempts to recreate another culture is highly offensive, especially when considering the western role in colonialism, slavery, internment, segregation, seizure of indigenous lands, etc. So from now on, please look beyond the purported humour or appeal of stereotypical, racist costumes and instead, respect other cultures’ physical appearances and practices. Do not limit a culture to a single identity. Do not culturally appropriate if you are incapable of assuming the discrimination which PoC have fought and continue fighting to overcome. Remember that another person’s culture does not exist to serve your Halloween joke or exotify your festival look. Rather, it allows us people of colour to celebrate our individualism, our history and our progress — all of which provides us with a sense of self, unity, and purpose.

Becca is a intersectional feminist with major heart eyes for Yayoi Kusama and David Bowie. When she’s not studying literature and environmental policy, catch her posting on her insta and daydreaming about the power of the universe.